My inbox has been inundated with people freaking out about recent papers and articles claiming that grass-fed beef is NOT going to save the planet. Basically, these scientists are ignoring important research and not looking at the full picture. While there’s still work to be done, many have proven that yes, in fact, grass-fed beef IS better for the planet.

I’ve found there are three reasons why people are conflicted about eating meat. The environmental argument is just one. We’re also fed a lot of misinformation about the nutritional implications of eating meat and conflicted about the ethics of eating animals. I get it. While I don’t argue for factory farming, I do offer some logical, concrete reasons for why meat, especially grass-fed beef, is one of the most nutrient-dense foods for humans and according to the principle of least harm, large ruminants like cattle are the most ethical protein choice.

For more about the nutritional benefits of meat, read this post

For more about the ethics of eating animals, read this post and this one

Ok, back to the recent environmental posts claiming cattle are ruining our planet…

In this post by George Monbiot, he tells us that, “Grazing is not just slightly inefficient, it is stupendously wasteful. Roughly twice as much of the world’s surface is used for grazing as for growing crops, yet animals fed entirely on pasture produce just one gram out of the 81g of protein consumed per person per day.”

The problem with the above statement is that grazing is not wasteful at all. When done correctly, grazing animals benefit the land. They provide vital nutrients and important bacteria through their manure, and their chomping stimulates new grass growth, which can help the plant sequester more carbon. Their overall impact on the land helps it hold onto rainfall more effectively, especially in brittle environments. Monbiot points out that pasture animals graze on more land that is cropped, but this assumes you can crop every inch of land on the planet. You can’t. About 70% of the Earth’s surface is only suitable for grazing, due to water scarcity, topography, poor soil, etc. His statement is incredibly misleading. Cattle and other ruminants can convert food we can’t eat (grass) on land we can’t grow crops on to nutrient-dense human food (beef) while having a beneficial impact.

Monbiot’s suggestion that we swap out all of our animal protein for soy because it’s a better use of land makes no sense. Maybe he should move to Kenya and tell the Maasai that they need to switch to farming soy instead of herding cattle. Let’s see how that works for their nutrition and land health!

And in Grazed and Confused, a special report by the FCRN that spent 2 years reviewing over 300 papers looking at the climate impact of livestock, researchers conveniently left out several pieces of important research that contradicts their findings. A detailed response comes later in the post…

But first, I want to address the inevitable question that comes up every time, “How can we feed the world if everyone switched to grass-fed beef tomorrow?” Please folks, this is not a relevant question in the debate. There are way too many people on earth. This is like asking me how I can possibly fit 200 people in my Subaru Impreza. I can’t. We have far outstretched our carrying capacity. Eating more soy will not fix this. Our population is doubling approximately every 35 years. Also, here’s another important question: is our current industrial agriculture and big food system working? I think not. Are we feeding people well and not harming the planet? No, we’re not. Is grass-fed beef better for humans and the planet? Is it utilizing solar energy better than lab meat and soylent? Yes, it is. Below is a diagram I tend to use again and again…

While I have some good knowledge on the subject of soil carbon sequestration, I’m not a soil expert. I’m a dietitian. Luckily, I’m friends with lots of experts! I reached out to my network and have two responses to post, with permission from the authors. The first is from Dr. Jason Rowntree of Michigan State University and the second from Russ Conser of Standard Soil. They sent me the detailed and well-cited responses below.

Here’s the CliffsNotes version:

- Cattle can convert food humans can’t eat (grass) on land we can’t farm.

- It’s difficult to replicate results of carbon sequestration in different locations due to issues like variation in soil quality, type of grass, and rainfall. What works in Virginia or Vermont probably won’t yield the same results in Nevada or Brazil.

- Grass-fed cattle can actually INCREASE biodiversity. Eating more soy will not do this.

- Monocropping plants like soy, wheat and corn are NOT inherently, ethically “better” or “cleaner” human food than grass-fed beef because they’re plants and not animals. Just, no.

From Jason Rowntree:

There have been recent reports that range from the acknowledgement of grazing management positive influence of ecosystem services, but not as an efficacious tool in reducing atmospheric CO2 to the denigration of grazing livestock as viable components of terrestrial landscapes.

There is a large and ever-growing database, mostly not acknowledged in the recent reports, documenting the positive impacts of grazing on soil carbon along with improvements in other ecosystem services that is consistent with what Allan Savory has been saying for years. To put these numbers into perspective a mid-size car emits around 1.28 metric tons of carbon (converted from carbon dioxide) annually into the atmosphere.

For reference, Allan Savory’s TED talk:

In 2001, Rich Conant and Keith Paustian, at Colorado State University, published a meta-analysis of 115 ranches from a variety of global environments indicating a mean annual 0.54 metric tons of carbon sequestered per hectare (ha) demonstrating the capacity for soil to capture and store carbon. In 2011, Teague et al. investigated the impact of high and low continuous grazing as compared to adaptive multi-paddock grazing (AMP) in Texas (the approach advocated by Savory) and indicated the AMP treatment had an annual 3 metric tons of carbon sequestered in the soil above and beyond that of the continuously grazed treatments.

USDA ARS scientist Alan Franzluebbers, has indicated high potential in the eastern US as well. In Nature, Machmuller et al, report over an 8 metric ton annual increase in carbon sequestration over a 3 year period following the conversion of degraded cropland to grazing land in Georgia. For context to meet an overall carbon sink (or storage capacity) for a Midwest grass-finishing beef system, our work indicate a needed 0.89 metric ton carbon sequestration to offset the entire footprint, including that from enteric methane emitted by cattle. This seems plausible based on the existing carbon sequestration literature.

Finally, the most downloaded manuscript in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, for 2016-17 cites the beneficial components of AMP and conservation agriculture on North American food production. The authors, of which Rowntree is one, estimate that if these conservation approaches were completed on 25% of our crop and grasslands, the entire carbon footprint of North American agriculture could potentially be mitigated.

Holistic Management is used by thousands of practitioners over millions of hectares of land. Proper adoption of animals to landscapes over a variety of precipitation levels is an efficacious land management tool. We have been on many of these ranches. Our laboratory is currently summarizing a large Patagonia dataset with ecosystem measurements on over 2 million hectares of land mostly managed holistically, that is, using a decision-making framework that helps land managers to move toward their goals in a way that is economically, ecologically, and socially sound in their context. Attempting to reduce the complexity of land management to just animals and time in a reductive scientific environment, is no different than splitting hydrogen from oxygen to study water.

Jason Rowntree, Michigan State University

From Russ Conser:

I feel compelled to comment on a new paper by Wolf et. al. (2017) Revised methane emissions factors and spatially distributed annual carbon fluxes for global livestock on GHG’s (including methane) that came out last week and that is directly related to the talk I gave at The Grassfed Exchange. The paper has gotten a lot of press with an effort to offer its results as supportive of an increasing role for livestock in planetary methane emissions. In short, whereas the paper is generally solid in its own underlying analysis, the attempt to extend conclusions beyond its own analysis falls short in my opinion.

Basics – The paper is a modeling, not a measurement paper. The authors did a more meticulous job of translating updated estimates by country (and even county in the US) into total methane and CO2 emissions for all livestock. Aside from a few assumptions whose implications are not immediately clear (e.g. forage = total animal requirement less documented feed input), it would seem that the overall estimates are sound. But in extending its conclusions, it falls short on 2 important aspects at least in terms of impressions:

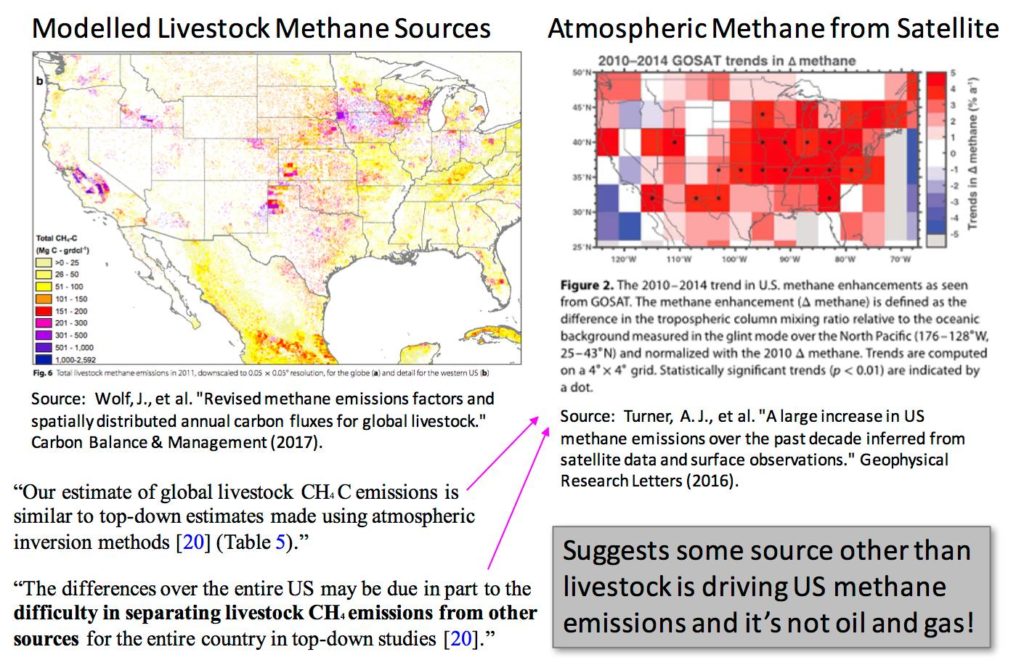

1. Spatial Distribution – In the image above, I compare Wolf’s new modeled source map to the Turner map of actual measurements and find a very poor match for the US. It’s somewhat hidden in the text, but I agree with a short statement this implies likely emissions from non-livestock sources – kind of contrary to the point they were making. It’s just a hypothesis, but I would argue this is just another clue that the missing methane emissions MAY be coming from bare or otherwise anaerobic soils on conventional row-crop land (and to some extent on degraded pasture) – which does fit the Turner map.

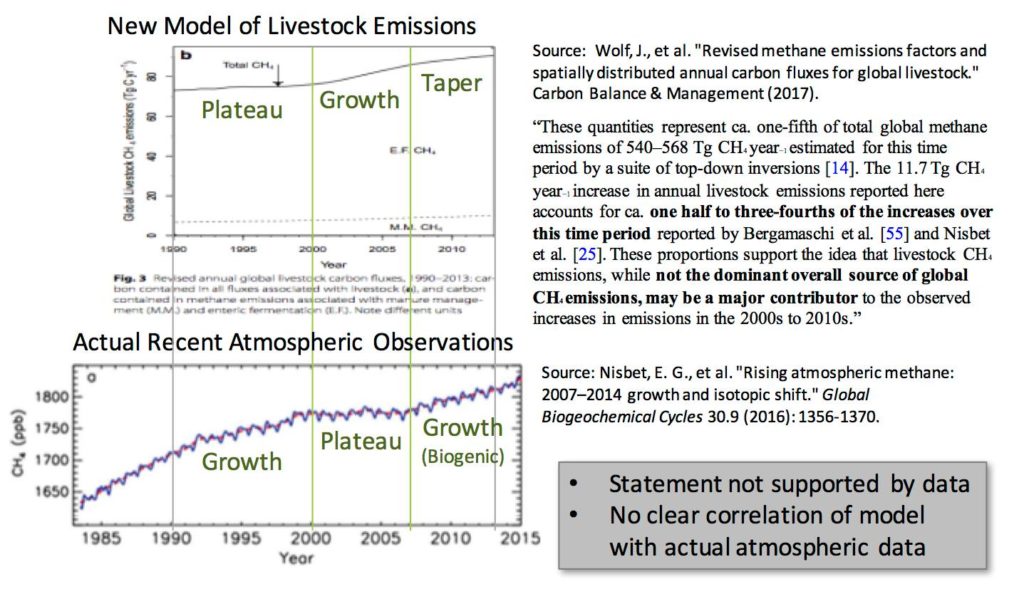

2. Temporal Distribution – In a slight of hand, the authors try to get away with saying that because there is a rise in both modeled livestock emissions and atmospheric measurements from the early 2000’s to the 2010’s, they must be related. But upon closer inspection of comparing their new data with the cited Nisbet paper (image below), we see a mismatch. The rise in modeled global livestock emissions is from 2000-2007 occurs during the period when atmospheric methane actually plateaued. Then the rise in atmospheric concentrations occurs at a time when the growth in livestock emissions taper off. I have annotated in attempt to make clear. For those not aware, we know from Nisbet’s paper (and others) that the post-2007 rise is biogenic related to ag somehow, and not fossil fuels.

Finally, one related comment not addressed directly in the paper. Much of the growth in US methane emissions comes from increased use of manure ponds for dairies (especially California) instead of letting manure oxidize in pastures. These ponds are high methane emitters. Now, California has put in place options to get carbon credits for putting anaerobic digesters on those methane sources. This fits nicely into the regulatory mentality of “additionality” – i.e. something else you would not do unless someone paid you to. But this is just insanity to me to pay people more money for cleaning up their own messes they created by diverting from the natural system. To me, this paper just underscores weaknesses in our current industrial farming system.

Russ Conser, Standard Soil

What to hear more?

24 thoughts on “Amazing Grazing: Why Grass-Fed Beef Isn’t to Blame in the Climate Change Debate”

Fantastic article, well done!

Once you go grass fed you will never go back.

I buy 1/4 of a grass fed cow in bulk from a family farm in my area that looks after the cows and the land very well.

They deliver it to my front door and even help me pack it into my freezer.

I think that is the way of the freezer, micro farming and farmers markets.

Knowing your farmer, knowing where your food came from.

It gives you a better appreciation for your food and you waste less.

Great reply, so nice to see the comprehensive

science. You must have spent all your free time at Grassfed Exchange with the experts that were all there.

I read a lot of the replies to Monbiot’s article. It is amazing how individual food choices are like religion.

It is not possible to drive change in someone once they have affirmed a commitment to one’s dietary religion.

Data doesn’t change behavior.

It is disturbing how loud the vegan / vegetarian voice is in public media.

But grassfed beef is now a many billion $$ business!! Someone is listening to us.

I had two couples show up at my farm store. They traveled for 2 hours looking for non CAFO “clean” food.

Interestingly they had not read any of the Paleo LCHF literature u are part of. They didn’t know what the word FOODIE was.

They were searching for grass fed food just from articles in magazines like TIME and common media.

Regards

Ike

You say that:

“Monbiot points out that pasture animals graze on more land that is cropped, but this assumes you can crop every inch of land on the planet.”

I make no such assumption. On the contrary, I pointed out, as clearly as I know how, that land now used for grazing would be better left or returned to nature, through rewilding. How was that difficult to understand?

By moving away from animal farming, we could release vast areas of land for nature, with tremendous gains for the living world.

It is worth repeating – as everything seems to need repeating in this debate – that only 1g of the 81g of protein we consume (on average) every day comes from animals fed only on pasture. Yet around twice as much grazing land as cropland is used, worldwide. Yes, grazing is a phenomenally wasteful use of land, and a massively disproportionate cause of environmental destruction.

Ok.

Saying that only a percentage of animals we consume are raised on pasture does not negate the huge benefits ruminants have on the land, or that we shouldn’t strive to have MORE animals on pasture. This is like saying, 20 years ago, that organic vegetables are such a small percentage of what’s on the market, so we should just give up and all eat conventionally produced vegetables and grains.

Over 70% of the earth’s surface is only suitable for grazing, so yes, it does make LOTS of sense to have more land in pasture for grazing than in crops. 85% of the cattle in the US are grazing on land that can’t be cropped – is this a “waste” of land?

If you’d like to remove pasture-raised cattle, bison and other ruminants and return it to “wild”, are we not allowed to eat them? Shall we only allow wolves and hyena the nutrient-dense protein of these animals, or can we hunt them and eat them? Red meat is incredibly nutrient dense a a fantastic food for humans. As we run out of cropland due to human sprawl, and more humans eating crops, are we to simply allow the “wild” to live and thrive on pasture? What do we do in areas where crops can’t thrive due issues to poor water availability, altitude, bad soil quality? Shall we tell these populations that thrive on animal products that they must now start trying to crop wheat or soy, or import rice and fresh berries from far away and allow their herd animals to roam free and die a “natural” death?

If we are going to convert the rest of the arable land on the planet to crops to feed humans, this would mean destroying large forested areas and tilling up land – these processes release carbon and destroy biodiversity. Well managed cattle, bison, and other ruminants on pasture INCREASE biodiversity and enhance the water holding capacity of the soil. Their “waste” fertilizes the soil.

I love the film you narrated, How the Wolves Changed Rivers. It really seems like you get the concept of how important natural cycles are. We can mimic that through electric fencing, intensive grazing, and harvesting of ruminants. Yet, it honestly seems to me that there’s a gigantic disconnect happening between “nature” and “human interaction”. Humans ARE nature. We need to work WITH nature to produce our food. Cropping is not working WITH nature. Intensive grazing techniques do exactly this.

How shall we return nutrients back to land that is used for crops? Fossil fuels or animal products? The soil bank needs to be replenished. How shall we get our plant-based fats – use valuable cropland to grow rapeseed (canola) and high energy processes to process it, or import coconut oil and avocados? How about use the fat from animals that are raised on grass, improving the soil and sequestering carbon?

Have you ever grown your own food? I live on a multi species farm. We produce both vegetables and pasture raised animals. The animals are rotated through the farm IMPROVING the quality of the land they’re on. Crops do not improve land, they drain it of nutrients and these nutrients need to be replaced. We replace the nutrients that the vegetables have taken with animal inputs. It’s a relatively closed loop. Are you saying that we should instead convert all the land we use for pasture to soy, corn or wheat? How is this a closed loop? Is this maximizing solar capture? If the planet has limited resources, how best can we recycle these resources for human food production?

Again, if you truly think that pasture land should be in “nature” then why can’t humans utilize natural cycles like this for food? Rewilding would mean ruminants like deer would return, and they would need to be managed with other animals like wolves. Ruminants being managed by predators. In well-managed grazing systems, we can mimic this with rotating cattle and harvesting them. We’re both arguing for nature – however it honestly seems that you aren’t acknowledging that humans are, and have always been, nature too. Cropping works against nature.

George knows all that stuff, he makes his money by being controversial though, so you won’t hear him backing down on grassfed beef anytime soon – he tried it once and it evidently produced a dint in earnings so he’s back on the bandwaggon, beating that drum, gettin’ those hits and clicks! If he truly believed in this stuff he’d put his money where his mouth is.

That was really really well said. Thank you! You said it better then I could have. I came upon this great article arguing with a vegan online. She just can’t seem to get it. I’m sending her the article and clipping out important parts. She’s at least engaging in a thoughtful discussion and not completely unhinged like the ones that threatened farmer’s and accuse meat eaters of being murdering rapists.

In seasonal humid environments (environments with a wet season and a dry season), grazing animals are nessecary for the ecosystem to function with the most important functions being a good water cycle, to have the water infiltrate into the soil and not evaporate out again, and to avoid soil erosion which of course is tied to a good water cycle.

In humid environments (constantly wet environments) animas are not nessecary to the ecosystem to achieve these functions, so removing the animals would usually improve the ecosystem, but that is only because the grazing management is being practiced is poor and changing that into planned grazing would improve the ecosystem more then taking the livestock out of it.

And I agree with Diana that grasslands are way better for the ecosystem compared to cropland, you could watch this 9 min. video, I think it gives a very good proof and understanding of that. https://vimeo.com/207541530

If he turned his fields into cropland, he would have way less diversity, he would have soil erosion down into the river contributing to damage on coastline ecosystem, he would need a lot of equipment, he wouldn’t improve the soil as fast, he would maybe need to cut some trees down etc. George, you need to focus on changing the management of the livestock, that is way easier than trying to remove them.

Louis, Just want to note that I believe animals are just as important to ecosystem function in humid/constantly wet environments as arid ones. The video you link of Don Jackson’s place in South Carolina is but one example. Without animals, such environments become a brushy mess that plateau in their productivity. With animals they keep cycling carbon and water in a circle that catches even more solar energy.

George Monbiot, I have been curious whether you have responses to some of the literature evidence mentioned above in the article, especially the Teague, Rowntree, et.al., 2016 paper in JSWC. Thank you.

George, let’s bring it out of the abstract and bring it to the ground level to an actual farm. I would like to know what we should do on our ~ 620 acres of highly erodible, heavy clay soils on rolling hills here in VT that would meet our ecological, social AND economic goals other than grass and cattle/sheep? I don’t think there is any amount of evidence that would convince me to put a plow in the ground to grow and annual crops. So, perennials? maybe grasses shrubs, and trees poly-culture. What’s my cash crop if not ruminants? Permaculture? Show me an economically working permaculture model scaled up. You suggest letting it re-wild. If I let it re-wild, would I then have to go get a job in town? Or maybe I should start a logging business 25 years down the line along with cultivating mushrooms. I guess I could charge people to hunt and forage on our property, maybe 10 years down the line. Though, maybe you’re aware of the logistical and financial challenges of multiple enterprises? Do you have a business plan for that? I’d hire you, $8/hr. We can debate numbers and data until we are blue in the face (and I tend to agree with those with the numbers and data arguing against you) but when it comes down to it, no idea will work if it does not take people into account. Mainstream environmentalist love to kick people off the land unless it’s to recreate and spend leisure time. Then those displaced people get to move to the suburbs and cities and have what kind of ecological footprint?

This seems a debate about semantics or hair splitting to me.

Surely holistic land management IS a form of rewilding, just one that incorporates the hundreds of thousands of years old influence of humans as one of the predators. At the very least one would have to concede that it is movement in the direction of rewilding from the mainstream systems for meat production. So why are we arguing? Given the context I can’t see why a farmer who cares about their land, animals and the environment should be pitted against the likes of George who as a writer who works to protect the environment, the land and animals. Everyone here would agree that CAFO’s are an environmental disaster, lets get them shut down and then we can have a conversation about the best way to manage the land that isn’t clouded by so much bullshit (pun intended 😉 )

I think any attempt to “re-wild” The Great Plains would be a failure. The habitat is too fragmented to support huge herds of bison roaming free. Yeah, I’d love to see that, but it’s a fantasy. Can you imagine bison trampling all the corn and wheat fields, and running through downtown Oklahoma City? Then add in the wolves and other predators needed to control the population. Can you see people tolerating wolves roaming free across America? Not to mention that humans were a major predator of bison. So why not have humans raise the bison and eat them? That is what is currently done with cattle. I would prefer to see bison brought back to prominence in this country and replacing cattle. We can’t just let them run free though, it wouldn’t work. They need to be managed like cattle.

As others have said, we also need animal agriculture to restore the soil. You just can’t rebuild soil at the same rate without animals. How do you propose to feed 9 billion people when petroleum based fertilizers run out?

I highly recommend you read David Montgomery’s latest book: Growing a Revolution.

I’m a big fan of George’s, and have two of his books lined up to read in my reading pile. And I have enjoyed watching his candid intellectual journey with diet over the years. I have been on a similar path, since I became engrossed in John Seymour’s writing back in the Eighties, and it always leads me back to plants AND animals.

One a purely philosophical level, good food production surely has to mimic Nature’s systems, because Nature has had millions of years to practice. Permaculture (whose definition is sustainable food production) aims to model cyclical systems that work in the most natural possible way. (And we ARE nature, as Diana says.)

So what do you find in wild Nature? You get herds of animals that roam the land in tight groups, avoiding staying too long in one place due to predation. You never get a single crop densely packed onto a field that sits bare for half the year. Similarly, you never get beasts confined into boxes crapping through a grate!

To extrapolate a slice of data and draw conclusions from it, such as, “A vegan diet is typically less damaging than an average omni diet, therefore we should all be vegan,” is a logical fallacy of schoolboy proportions. (Yes, the average vegan diet requires less land, water, etc., than the average Joe’s diet, but that does not mean that it’s optimal.)

The problem is NOT meat vs. plants. The problem is intensive, mono-culture, industrial farming, whether that is of plants or animals. Growing soybeans or corn in huge fields is catastrophic for the environment. Ploughing is catastrophic for the environment.

Our first priority, as George has written before, must be to protect the soil. No, that’s not good enough… we need to restore the soil! And the best way to do that is not to grow crops on it every year. Seymour recommends four years of crops followed by four years of grass cover, for example. Now, a meadow that is grazed not only sequesters more carbon than undisturbed grassland, but thanks to poo and wee its soil becomes far healthier too.

What’s more, what do we do if the oil runs out (before the soil does)? Will we have solar-powered Tesla tractors and combines that can run 20 hours of the day at harvest time? Or will we be forced to give up our nice middle-class privilege and return to the wildest forms of farming: rich rotations of plants and beasts? Pigs to clear the land after the grass or root vegetable breaks and de-weed the woodlands, cows to keep the grassland healthy, and goats to eat everything else.

Nature is not vegan. Not killing animals for meat does not mean we are not killing animals (large fields are biodiversity deserts), nor does it mean we have more animals. If we believe in Nature, if we believe in her wild ways, and if we want to maintain the richest growing environment possible, I’m convinced we must take responsibility and raise and manage beasts.

Dear George,

i used to be a fan of you, but your latest article regarding meat is missing the point by more than a country-mile.

The reactions before this (my) one have done a great job in explaining why you are in the wrong.

An ecosystem can be explained by the formula proposed by Einstein, E=MC^2. And in agriculture we try to mimic nature as much as we can. Because that is holistic and cyclic and therefore sustainable.

You not only propose to get rid of C2, but also C1 in the equation. That means that in your view any agricultural ecosystem equals plant mass…. and that’s it? How do you propose to control insects in croplands? How do you propose to keep wild animals from damaging the crops or small rodents? Do you intend to gather animal dung from rewilded areas to fertilize croplands? Etcetera, etcetera.

It is incomprehensible that people like you think that everything can be solved by simply eradicating animals. If you really think that such a 2-dimensional measure is going to solve everything, then you have a warped sense of the complexity of any healthy ecosystem.

Hey George, I’m a bit distracted here with a fire consuming everything around me but I had to weigh in. I raise cattle in a partnership with a conservation preserve in Sonoma County California. I was recently stopped by a visiting scientist who asked me why we had livestock on a nature preserve and my answer was that there was not enough extant wildlife to manage the biomass. I manage my animals as a wild herd. One group, all classes together year round. Electric fencing and frequent moves keeps them bunched and moving and has “rewilded” their herding instinct. They don’t know they’re domesticated, they are ruminants doing what is natural to them. My responsibility is to manage them adaptively and to the best of my ability in a way that enhances this ecosystem. I do that with planning, monitoring and adapting as needed via the decision making process known as Holistic Management. As such I am entering my 6th year in relationship with this scientific conservation preserve as part of their adaptive management plan. We use planned grazing to enhance ecosystem function and maintain/the grassland and savanna components of this land base. We are having a bit of a setback at the moment but will continue to facilitate these amazing animals not only as a proxy for long extinct mega fauna but in their own current and very necessary place on the planet. I do this as an alternative to the same destructive system you so eloquently oppose yet without your understanding, collaboration or support. That sucks. I work hard every day as do you trying to contribute to a survivable future for all species. I know we are on the same team but when I read an article that cherry picks data that doesn’t apply to my management to suggest that I’m not helping it leaves me feeling a bit bitter and taken for granted. We need more advocates. Please come visit and learn more about what you are writing about. We need you. Apologies for my grammar and spelling, I’m up late in the night after pivoting around a wild land fire that just consumed the 3,000 acres we manage. A serious setback but one that we will no doubt manage our way out of holistically.

It’s all been said…. OK so we only get an average of 1/80th of our daily protein needs from beasts on the grasslands… that is 1/80th we would need from elsewhere if we didn’t have them… then you need to add in the supplements essential to a vegan diet… the vitamins, trace elements etc that cannot be achieved outside the lab without animal input, but the final part is… if the whole world was vegan… the only places for any other species than our own would be where humans never went…. what poverty of experience to never have the companionship of a dog, to never watch the grace and elegance of a cat.

The uplands of Britain are biodiversity rich… with species that have lived in such an environment for millenia, the forests were largely cleared in prehistoric times, not for grazing or farming, but to use the timber for building, and to build where any trouble could be seen approaching. Creatures have eveolved for just that place.. would you eliminate them by having it revert to the forests, for which we no longer have the wildlife?

If you import wolves to hunt the deer, how would you protect deer and wolves from cars, and people from wolves?

So many things simply not thought through!

I’m a big fan of George’s, and have two of his books lined up to read in my reading pile. And I have enjoyed watching his candid intellectual journey with diet over the years. I have been on a similar path, since I became engrossed in John Seymour’s writing back in the Eighties, and it always leads me back to plants AND animals.

One a purely philosophical level, good food production surely has to mimic Nature’s systems, because Nature has had millions of years to practice. Permaculture (whose definition is sustainable food production) aims to model cyclical systems that work in the most natural possible way. (And we ARE nature, as Diana says.)

So what do you find in wild Nature? You get herds of animals that roam the land in tight groups, avoiding staying too long in one place due to predation. You never get a single crop densely packed onto a field that sits bare for half the year. Similarly, you never get beasts confined into boxes crapping through a grate!

To extrapolate a slice of data and draw conclusions from it, such as, “A vegan diet is typically less damaging than an average omni diet, therefore we should all be vegan,” is a logical fallacy of schoolboy proportions. (Yes, the average vegan diet requires less land, water, etc., than the average Joe’s diet, but that does not mean that it’s optimal.)

The problem is NOT meat vs. plants. The problem is intensive, mono-culture, industrial farming, whether that is of plants or animals. Growing soybeans or corn in huge fields is catastrophic for the environment. Ploughing is catastrophic for the environment.

Our first priority, as George has written before, must be to protect the soil. No, that’s not good enough… we need to restore the soil! And the best way to do that is not to grow crops on it every year. Seymour recommends four years of crops followed by four years of grass cover, for example. Now, a meadow that is grazed not only sequesters more carbon than undisturbed grassland, but thanks to poo and wee its soil becomes far healthier too.

What’s more, what do we do if the oil runs out (before the soil does)? Will we have solar-powered Tesla tractors and combines that can run 20 hours of the day at harvest time? Or will we be forced to give up our nice middle-class privilege and return to the wildest forms of farming: rich rotations of plants and beasts? Pigs to clear the land after the grass or root vegetable breaks and de-weed the woodlands, cows to keep the grassland healthy, and goats to eat everything else.

Nature is not vegan. Not killing animals for meat does not mean we are not killing animals (large fields are biodiversity deserts), nor does it mean we have more animals. If we believe in Nature, if we believe in her wild ways, and if we want to maintain the richest growing environment possible, I’m convinced we must take responsibility and raise and manage beasts.

Very well articulated response!

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Make America GRAZE Again! - Sustainable Dish

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Whole30 Beef and Broccoli Bowls (Paleo, Low Carb, Keto Friendly)

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] What is so bad about grain? – Live | Sleep | Dine | Primally

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Why you should eat like me - Allycins

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] I’m a Dietitian and Here’re 11 Reasons Why I’m Team Meat

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Pumpkin Beef Skillet- 10 Minute Dinner! – Wonderfully Made Nutrition | Functional Medicine Dietitian in New Jersey